Interview with Refugee Outreach and Refugees Network, on 7 March 2022.

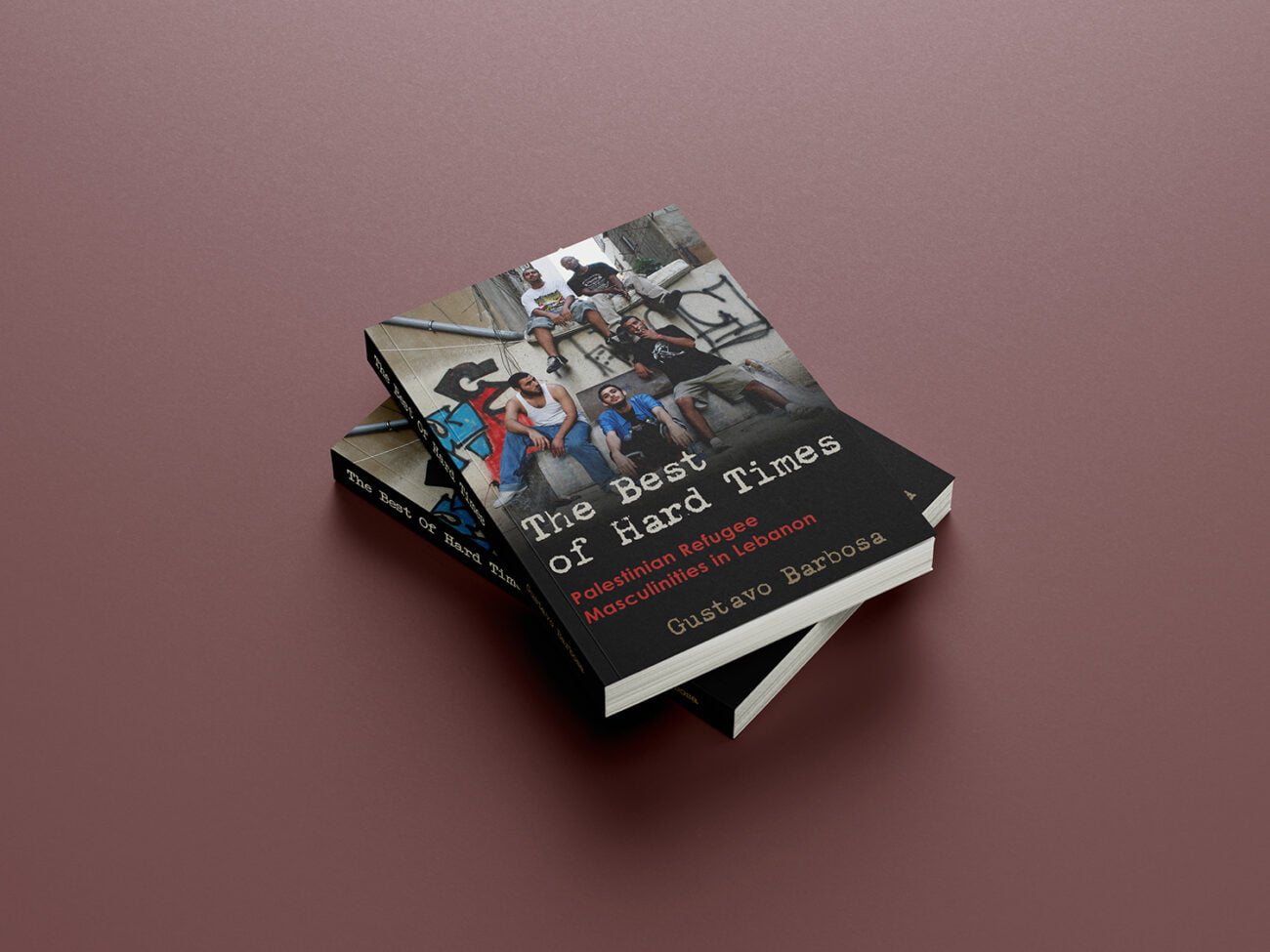

“This essay presents one of the arguments developed by the author in his book The Best of Hard Times: Palestinian Refugee Masculinities in Lebanon (Barbosa, 2022).”

In this short essay, I argue for the full historicity and pliability of masculinity, which changes from place to place and time to time. Based on fieldwork conducted in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in the southern outskirts of Beirut, where I lived for one year and conducted research for two, I demonstrate that the shabāb, the lads from the camp, faced with unemployment and the de-mobilization of the Palestinian Resistance movement, in its military form, cannot replicate the heroic persona of their forebears, the fidāʾiyyīn, who exude virility when narrating their deeds. As may be implied from this already, based on shabāb’s biographies, I problematize what Marcia Inhorn (2012) has ironically labelled “hegemonic masculinity, Middle Eastern style.”

I develop my argument in three moves. First, I provide the reader with historic scaffolding, so that s/he can understand not only why masculinity has changed from one generation to the next, but also why gender, as a concept imbued with notions of power, works well to describe the fidāʾiyyīn’s lives, but not the shabāb’s. Second, I provide some ethnographic evidence to this argument. I finish by addressing some of the theoretical implications of my reasoning.

For the historic scaffolding, I quote from what I consider as the best documentary about Shatila, the movie Roundabout Shatila (2005), by Maher Abi Samra. Even though a bit dated, the quote, illustrated by the film frame below, shows how Shatila is placed at the centre of various circles of causation, all highly complex. That means, in practice, that Shatilans today, including the shabāb, have very little control of what at the end comes to determine their lives.